I met someone recently—someone I’d spoken to online—at a party I attended not long ago. In person, though, something felt immediately off. Not because of chemistry or the lack of it, but because of an almost compulsive need he seemed to have: to look down on everything around him.

The party wasn’t good enough.

The music wasn’t up to the mark.

The people weren’t interesting enough.

Nothing passed muster. Everything required commentary, and all of it was dismissive.

He told me he was 22. And instinctively, I wondered if this was an age thing. But then I stopped myself. I was once that age too. I don’t remember needing to belittle an entire room to feel significant within it.

What unsettled me more was the familiarity of it. I’ve encountered this posture before—among people I’ve known, been friends with, sometimes even admired at one point. A certain self-appointed elite, defined not by kindness or depth, but by what and whom they reject. How others dress. How they speak. What music they like. Where they come from. Everything becomes a metric for exclusion.

I’m not pretending I’m immune to prejudice. I’m not. I know exactly where mine lies.

I don’t tend to judge people by caste, class, race, or colour. But I do judge—quietly, perhaps arrogantly—on intellectual and emotional grounds. Empathy matters deeply to me. Curiosity matters. The ability to question inherited beliefs matters. And yes, I struggle with people who are blinded by unexamined faith or rigid dogma. That is my bias. I own it.

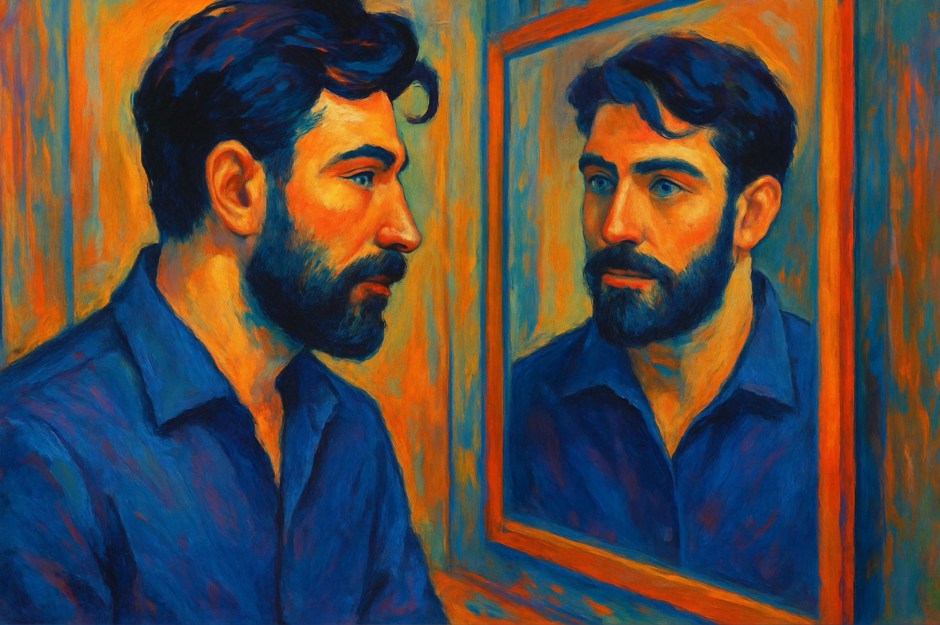

So the uncomfortable question arose: was I doing something similar to him, just dressed in better language?

I don’t think it’s the same. Or at least, I hope it isn’t.

Because there is a difference between choosing not to engage, and actively deriding. Between recognising incompatibility, and making contempt a personality trait. What I witnessed wasn’t discernment—it was dismissal masquerading as sophistication.

There’s something deeply sad about believing that to appear intelligent, dapper, or “above it all,” one must constantly signal what one is not. That one must shrink others to inflate oneself. It’s a brittle kind of confidence, and it cracks easily.

Perhaps age does play a role. At 22, there is often a frantic need to impress—by saying the right things, having the right opinions, aligning oneself with the “correct” tastes. Sometimes that performance hardens into habit. Sometimes it softens with time. I don’t know which way it will go for him.

What I do know is this: I don’t need to pull anyone down to feel whole. I don’t need to sneer at a room to belong in it. If I don’t resonate, I can simply step away—with grace.

We live in a world already cruel enough, stratified enough, lonely enough. Choosing empathy over elitism isn’t naïveté; it’s resistance.

And perhaps the real marker of maturity—emotional, intellectual, human—is not how sharply we judge, but how gently we hold our differences.

You must be logged in to post a comment.