I have often spoken about death with what I believed was realism. When I spoke about Zach and Xena’s imminent passing this year, I believed I was simply acknowledging reality. The doctors had already told… More

Our Love

I let you go today;

I let you go, to sleep;

You are not in pain now

I, yet alive, must weep –

I cry for the love I had:

That which you showered on me;

I bid Death take it away

And it can no longer be –

I saw your body burn –

I saw the love you gave die –

I have met Death before –

I no longer ask why.

If I asked it of you,

I know you would stay –

Alive, you hobbled to me,

Though cancer barred your way.

But I sought peace for you –

Love makes it very sad –

I had you put to sleep,

Now it drives me mad –

You’re no longer in pain

So Death commands I weep –

Because as I let you go –

Our love I get to keep.

My Warrior Princess

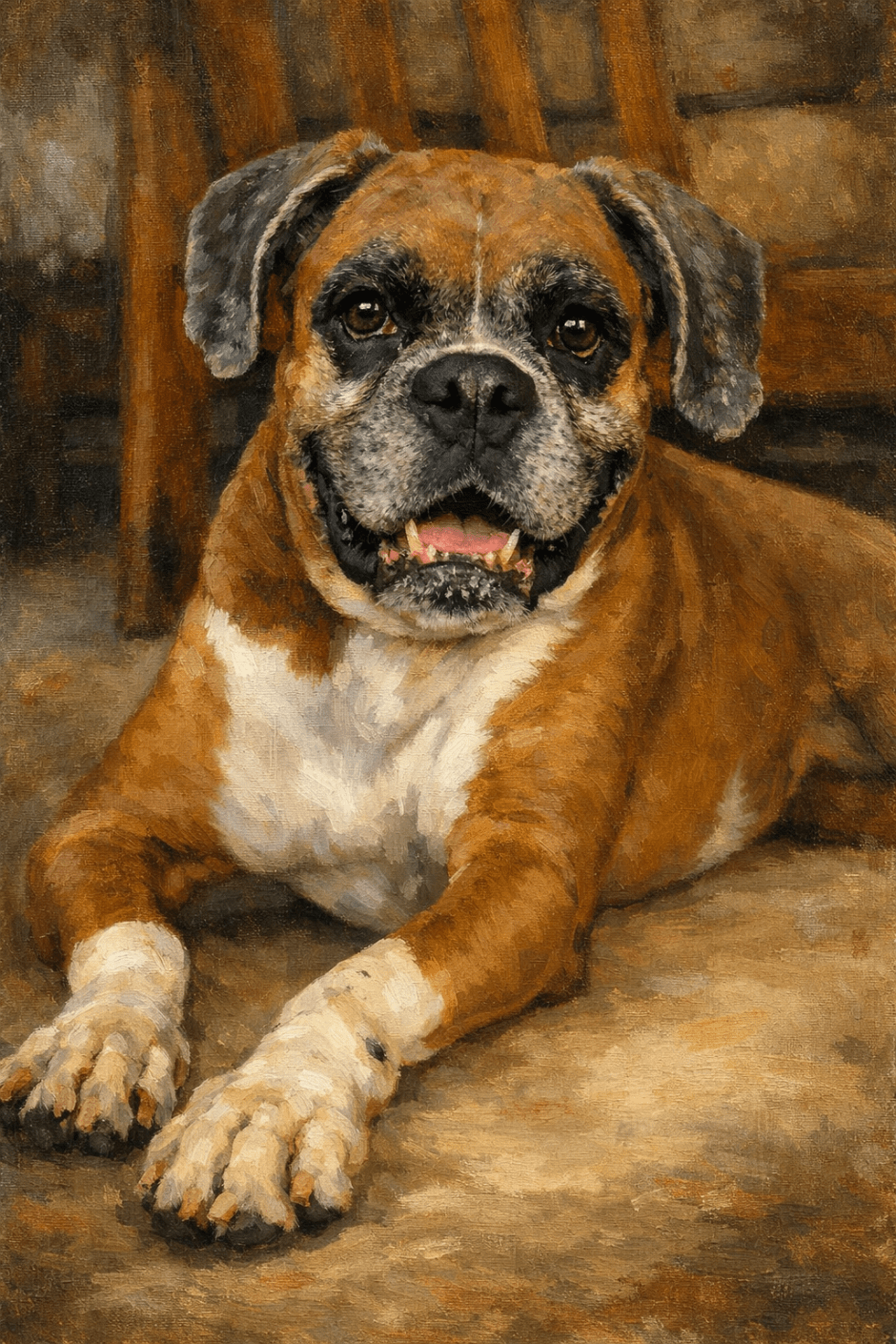

Today I lost Xena.

She began bleeding in the morning. Through the night I had stayed awake beside her, watching over her as I always did. Those quiet hours had passed without incident. It was only in the morning, when I finally lay down to rest, that things changed. Within an hour she began bleeding heavily — blood, clots, and histamine from her anal area. Something inside her had clearly given way.

In that moment I knew what I had been trying not to admit for a long time.

It was time to let her go.

My brave girl had already carried more suffering than most creatures should ever have to bear. Mast cell tumours had spread across her body — around her eyes, along her paws, across her chest. Every day was a routine of care: cleaning wounds, changing dressings, wrapping paws, protecting the tumours near her eyes so she would not scratch them. The tumours on her chest needed constant dressing and covering with a T-shirt, though she hated wearing it because her thick coat made her feel unbearably warm.

The lipoma beneath her tail caused problems. Because of her bladder issues she developed incontinence. We tried diapers, but they pressed painfully against the swelling. So we removed them and learned to manage things differently. Her paws needed bandaging. Some days one paw, some days two. Every walk required shoes to protect her feet, and afterwards we would remove them, clean her, and redress the wounds.

She also carried arthritis and spondylitis in her ageing body.

My poor girl suffered so much.

And yet she was so brave.

When she first came to me in May of 2014, she arrived alone from Bangalore in a tiny crate on a flight. When I first saw her, she was hardly more than a foot long — a tiny thing with a black muzzle, a black face, a white diamond on her back, and flashy white socks on her paws. Even then she seemed impossibly courageous.

That is why I named her Xena — the Warrior Princess.

And she lived up to that name every day of her life.

Her first mast cell tumour surgery came when she was barely a year old. Two more followed over the years. Somehow we managed to keep bladder stones at bay with careful home care — coconut water became part of her routine. But by the time she was nine or ten she developed incontinence. Even then she handled it with quiet dignity. Because of a certain tick medicine, she developed epilepsy. She began treatment for that.

She was never a demanding dog. She learnt how to use the toilet in her fourth day in our home. She was barely two months old. She never fussed or troubled anyone for walks or toilet breaks. She simply did her business quickly and efficiently. But she had personality in abundance. She loved playtime. All of the toys were hers! She was not a sharer.

Xena was always “in your face”, always present. She followed me around the house like a small lamb, bounding beside me like a little goat.

On walks she was always off the leash. Perfectly obedient, yet delightfully independent. Every few steps she would turn around to check whether I was still behind her. That small habit, that constant glance back, was her way of making sure her world was intact.

Whenever Anand picked up the leashes to take the dogs downstairs, Xena would be the only one who returned to the room to check whether I was coming. And if I stayed back, she was the only one who would hesitate at the door, waiting for me.

She trusted me completely.

She was also the last of my dogs to have witnessed a different chapter of my life — a time when my aunts were alive, when the house was full, when my circle of friends was large and laughter came easily. She was there through the storms as well: through heartbreaks, through struggles in my relationship, through the loneliness of COVID, through the grief of losing my aunts.

Through it all, she stayed.

Patient. Loyal. Watching.

Waiting by the door for my return.

I have known this heartbreak before. When Zoe left, a piece of my heart went with her. And now Xena has taken another piece with her.

These girls of mine — Diana, Zoe, Xena, and now Zuri — they arrive quietly into my life and carve out enormous spaces in my heart. And when they leave, they take those pieces with them.

Today Xena has taken hers.

There is a vacuum where she used to be. Like Zach, I feel her absence intensely. I write this in the first 24 hours of losing her. I haven’t shut off the alarms for her medicines. Or her coconut water time. Or emptied the two boxes filled with medicines for her tumours, her eyes, her chest, her anus, her paws. It’s all around me – spinning cartwheels…

But wherever she is now, I hope that my warrior princess has finally found what this world could no longer give her: rest. A state where there is no pain, no tumours, no dressings, no cones, no wounds to clean.

Only peace.

The suffering has ended for her.

The only one left to suffer is me.

Because I still do not know how to live in a world where hearts as pure as theirs — creatures capable of such boundless loyalty and love — are only given such a short time among us.

She spent her life looking back to see if I was there. Now I will spend the rest of mine looking back to remember that she was.

But you, you rest now, my brave girl. Your battles are done.

The Bitter Watches of the Night

I know what I have seen,

In the bitter watches of the night;

I know where my hands have been,

As they soothe your body in its fight.

I know what pain you bear,

As the cancer eats away at you;

I know what oath awaits me there —

To relinquish what love must do.

I’ve lost pieces of my heart before —

Five weeks gone, had Death cast his spell;

Yet I must again beg at his door,

Where painless mercy chooses to dwell.

It is for us, I keep you with me still –

Breathing and loving and aching –

But I must, by sheer force of will,

Think on your peace in his taking.

I have loved you and will always,

You’re my curmudgeon, my daughter –

This love is what stays, my child,

Long after you are dust and water.

You must be logged in to post a comment.