Born in the hazy summer of ’75, I straddle two worlds. A world where whispered secrets in hushed tones were the currency of connection, and the digital roar of today. A world where a clumsy fumble for the right cassette tape was the soundtrack to a Friday night, and now, instant access to any song ever conceived is at my fingertips. This liminal space, this bridge between the analogue and the digital, has shaped me, challenged me, and ultimately, liberated me. But my journey has been deeply marked by personal struggles, too, struggles that were often silenced in the pre-internet era.

Growing up, life wasn’t always easy. Being different in a less accepting time meant enduring the sting of prejudice, the isolation of feeling like an outsider. My father, a man of the Boomer generation, struggled to understand my sexuality. His alcoholism fuelled a volatile temper, and from the ages of 13 to 19, my home became a battleground. Physical and emotional abuse were a regular occurrence, a brutal consequence of his inability to accept who I was. These were wounds, both visible and invisible, that I carried in silence. In my generation, such experiences were often endured privately. We believed, or were led to believe, that this was simply “the way things were.” There was no readily available support network, no online community to offer solace or share similar experiences. Interpersonal relationships were forged in the crucible of face-to-face interactions, often fraught with the anxiety of revealing my true self, a self that was deemed unacceptable by my own father.

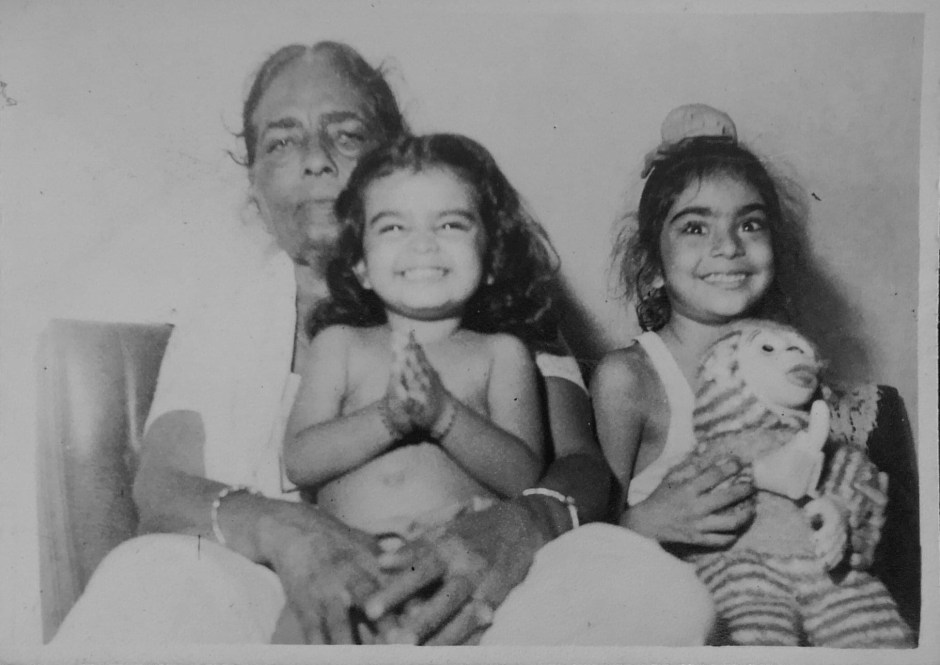

It was my sister, bless her open-minded heart, who offered a glimmer of understanding. She recognised that my sexuality was not something to be controlled or condemned. The women in my family, too, showed a degree of acceptance, though often tinged with a grudging tolerance rather than the wholehearted embrace that Gen Z enjoys today. Their acceptance, while appreciated, lacked the open-minded celebration of difference that now seems more commonplace. It was a different time, a time when even well-meaning individuals struggled to fully comprehend the complexities of sexual identity. Even my sister’s acceptance, though genuine, proved to have its limits. Years later, in my 40s, as she prepared for her wedding, she asked me to hide my sexuality for the sake of her in-laws. This request, from someone I considered an ally, cut deeply. It was a stark reminder that even those closest to us can sometimes falter when faced with societal pressures. It highlighted the subtle but pervasive homophobia that still existed, even within my own family. It was a painful lesson in conditional acceptance, a reminder that the fight for true equality was far from over. It was a blow, a betrayal of sorts, that echoed the silent acceptance of abuse that I had witnessed in my youth. But in my 40s, I had found my voice. I had learned to value my authentic self above all else. I told her, with a firmness born of years of struggle and self-discovery, that if I couldn’t be accepted for who I was, I would not be attending her wedding.

Ironically, it’s technology that has, in many ways, given me my voice. The internet, for all its flaws, has provided a platform to connect with like-minded individuals, to find community, to celebrate diversity. It has allowed me to explore my identity, to find my tribe, to finally feel seen and heard. In my early 20s, as the internet began to emerge, I tentatively sought connection, a lifeline to others who understood. It wasn’t easy. Access to gay media, information about gay lifestyles, and a broader understanding of how inclusive work cultures should function was limited. But even then, the seeds of connection were being sown. I found support, albeit in smaller measures, and began to understand that I wasn’t alone.

This generation, Gen Z, with their fluid identities and fearless self-expression, inspires me. Their willingness to challenge norms and push boundaries reflects a world I longed for as a child, a world where difference is celebrated, not condemned. They are the change, the adaptation, and I admire them for it. While I know they face their own battles against bigotry – for prejudice sadly persists – the ability to find support and community online is a powerful tool they wield, a tool we lacked in my youth.

The Millennials, perhaps, are the truly lost generation. Caught between the analogue world of my youth and the digital explosion of Gen Z, they seem to be a transitional generation, navigating a world in constant flux. For those of us born in the mid-70s, the change was gradual. We adapted slowly, absorbing the new technologies as they emerged. We experienced the world before the internet, and we witnessed its birth and evolution. This gradual transition allowed us to integrate the digital world into our lives without losing touch with the values and experiences of our past. It also gave us time to process and understand the changing social landscape, including evolving attitudes towards sexuality and gender identity. My own journey of understanding and self-acceptance was intertwined with this gradual shift. Through my studies in psychology and English literature, I began to understand the importance of empathy, acceptance, and celebrating diversity, lessons that were often hard-won in my personal life.

My 40s, finally, became my decade. It was a time of self-acceptance, of embracing my identity without apology. The scars of the past, though still present, no longer defined me. I learned to set boundaries, to refuse to tolerate disrespect, to live authentically and unapologetically. This newfound confidence, this refusal to “take shit from anybody,” is a product of my journey, a journey that spans the analogue and digital worlds, a journey that has taught me the true meaning of resilience and self-love. It’s a journey that has also taught me the importance of forgiveness, not necessarily for those who have hurt us, but for ourselves, to allow us to heal and move forward.

We, the generation born between ’69 and ’82, are indeed a unique breed. We are the bridge between two worlds, fluent in the languages of both. We remember the crackle of the radio and the flickering glow of the television, but we also understand the power of the internet and the potential of virtual reality. We value tradition, but we also question and challenge, driven by reason and critical thinking. We have seen the world change dramatically in our lifetimes, and we have adapted and evolved along with it. We understand where we come from, and we have a unique perspective on where we are going. Perhaps, then, it is our generation that is best equipped to lead, to guide, to bridge the gap between the past and the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.