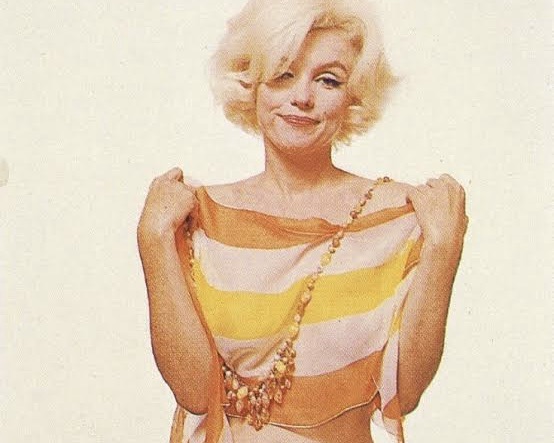

I was watching songs, clips, interviews of and on Marilyn Monroe today, and it took me back to when I first saw her on screen. I must have been seven or eight when I watched the unveiling of her statue in her iconic pose in The Seven Year Itch, mesmerised by that iconic moment—the white dress billowing around her, the radiant smile on her face. Back then, she seemed like a goddess, the epitome of beauty and joy. But as I grew older and learned more about her life, I realised how much that single image had cost her in reality.

That made me think about how much we, as individuals, shrink ourselves, twist ourselves, and dim our own light to fit the expectations of others. Earlier this week, a friend of mine—who once directed me in a stage musical—told me about a party he attended. There were Millennials and Gen Z boys raving about me, reminiscing about my performance in that play. The way I looked, the way I carried myself, the way I commanded the stage—those were the things they remembered most vividly. And it struck me, because I have never seen myself the way others apparently do.

For so long, I have felt like I wasn’t enough—not tall enough, not sexy enough, not thin enough, not thick enough. Always not enough. I have spent years looking in the mirror and seeing only what I lacked, never what I had. And I know this feeling has seeped into my relationships as well. I have always felt like the subordinate one, placing my lovers on a pedestal, convinced they were cooler, more desirable, more worthy than I was. My love for them made them grander in my eyes, while I shrank in my own.

Watching Marilyn’s documentary, I wondered how much of our self-perception is shaped by the expectations and judgments of others. She was adored, desired, envied—yet also ridiculed, diminished, and underestimated. Her beauty, her sensuality, the effortless way she captivated a room—she owned it, yet was punished for it. Even in 1962, when she filmed a nude scene for Something’s Got to Give, it was considered scandalous. And yet, decades later, it still holds power, still exudes that intoxicating mix of vulnerability and confidence.

In some ways, I see myself in her. I came out at 16, unapologetic about who I was. I have always flaunted my truth, never hiding my relationships, never pretending to be someone I’m not. I have loved openly, fiercely, without shame. And now, in a polyamorous relationship, I continue to live my life on my own terms. And yet—yet—that old, lingering feeling of inferiority remains. That quiet, insidious whisper that I am still not enough.

So I ask myself: How much of me have I given up to meet the expectations of others? How often have I dimmed my own brilliance to make others comfortable? How many times have I tried to fit into spaces and relationships that were never designed for me in the first place? And more importantly—why?

Marilyn was a woman who lit up the world, even as it tried to break her. And maybe that is the lesson here. That no matter how much the world tries to shape us into something smaller, something quieter, something more palatable—we have to fight to be ourselves. We have to own our space, our beauty, our chaos, our truth.

Because if we don’t—if we keep cutting ourselves down to fit inside someone else’s frame—what will be left of us in the end?

You must be logged in to post a comment.