Today, Mumbai votes in the BMC elections.

And I almost didn’t go.

Not because I don’t care — but because I am exhausted by a society that has lost its moral compass, and by institutions that no longer protect the innocent — human or animal.

I am an animal lover.

And what I’m witnessing in this country — especially in my city — feels like a slow, sanctioned slide into brutality.

Stray animals are being turned into a convenient villain.

Dogs who have lived alongside humans for generations are suddenly being described as a “menace”, a “threat”, something to be eradicated. Not managed. Not cared for. Removed.

And this language is no accident.

It is the language of a society that no longer wants responsibility — only control.

Instead of investing properly in Animal Birth Control programmes, vaccination, civic education, and enforcement of existing animal welfare laws, we are watching a dangerous narrative take hold: that animals must disappear so humans can feel comfortable.

That is not civilisation. That is moral regression.

What has shaken me most is not social media hysteria — it is the Supreme Court of India itself.

Judges of the highest court — the very institution meant to protect the voiceless — are asking animal welfare advocates to “take the dogs home”.

As if compassion is a private hobby.

As if the state has no responsibility towards animals it has failed to manage humanely.

During hearings, judges made remarks about dog bites that were steeped in fear, prejudice, and anecdote, not evidence or constitutional values. One judge asked whether a person bitten by a dog would have to “live with that mental state for life”.

To which Menaka Guruswamy, an advocate fighting for animal rights, calmly replied that she herself had been bitten many times — and stood before the court in perfectly good health.

That response should have prompted reflection.

Instead, what followed felt plebeian, reactionary, and disturbingly dismissive of science, law, and empathy.

This is the same court that speaks eloquently about dignity and rights — yet seems willing to reduce animals to disposable nuisances to appease public anger.

If the highest court can be swept up by populist cruelty, where does that leave the rest of us? And the animals we care for?

Mumbai Is Being Strangled — And No One Is Listening

In my own city, the assault is everywhere.

Relentless construction has turned daily life into a health hazard.

Protected mangroves — our natural lungs and flood barriers — are being cut down in the name of “development”.

The air is toxic. Pollution has kept me sick for months. My entire family is unwell.

Walking is an obstacle course.

Pavements are dug up. Roads are cratered. Traffic screams into your face, horns blaring without pause.

I cannot walk my dogs properly.

Sometimes, I cannot walk myself.

And yet, when people complain, they are bullied into silence — reminded of the “powerful people” others know, the influence they wield, the consequences of speaking up.

I won’t even get into how trees from the Sanjay Gandhi Park were cut down years ago or how the Aravallis are now in danger.

This is happening because there is no fear of the law anymore. Only machismo. Only intimidation.

Fear Is the Default State for Women

My mother and my sister live with fear — especially after dark.

Not abstract fear. Practical fear. The kind that makes you change routes, rush home, avoid confrontation, and stay quiet.

Women are not safe in this country.

And the most terrifying part is not crime — it is the belief that justice is reserved for those with money and power.

A woman was reportedly picked up outside a police station itself in Rajasthan — and nothing could be done.

If safety cannot be guaranteed there, what does law enforcement even mean?

Taxes Paid, Dignity Denied

I pay taxes — heavily.

And what do I get in return?

A city that makes you sick.

Institutions that sound cruel and careless.

A society eager to eliminate animals rather than confront its own failures.

A civic system where votes feel like deposits into a bottomless pit of corruption and indifference.

Every election promises change.

Every election delivers more money to those in power — crores of rupees were spent on the BMC elections right now — and more suffering to those without voice.

Including animals.

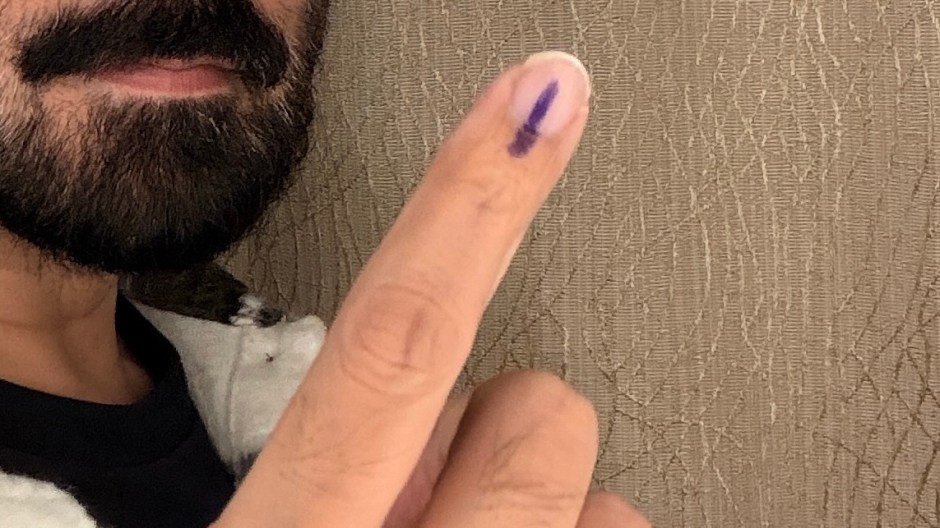

So Why Did I Vote?

Honestly?

I don’t know if my vote will change anything.

But not voting felt like surrender — and I am not ready to surrender my belief that compassion still matters, even if the world around me seems to be abandoning it.

This is not just about governance.

It is about who we are becoming.

A society is judged not by how it treats the powerful — but by how it treats the vulnerable.

And right now, we are failing — badly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.